"I hate the idea of a super, master race, and of a Big Brother, authoritarian America in which those, who are not exactly like the self-anointed 'real' Americans, are to be excluded, segregated, feared, hated, and ejected without recourse. I'm old enough to smell Nazi Germany whenever demagogues seek to revive it, no matter how tightly they wrap Old Glory around their lies."

Ron Friedman, The Hollywood Reporter, 2016

"It was only about, I would say, like four or five or maybe even six scripts that into the series we began to realize how weird we could actually get with that show. [Laughter] And then once it started it couldn't be stopped. It got stranger and stranger right up until the end."

Steve Gerber, Comics Interview, 1986

I know why I feel compelled to launch a recap series of G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero in 2025, in the midst of all of this, but I am struggling with how my compulsion fits in with the moment. America is being ruled by a idiotic autocrat who gets off on watching our armed forces show fealty to him, the human equivalent of a McDonald's bag that's been soaked through with french fry grease. I don't not think that harkening back to the jingoism of the Reagan era is an iffy idea (Ronald Reagan was also a bad president who let an entire generation of queer people die an agonizing, inhumane death, among other crimes).

But then I find quotes like those, from the man who essentially "created" G.I. Joe for animation (Friedman), and the man who led the series for the longest stretch of anyone (Gerber). Those quotes validate my need to write about this cartoon, this franchise, because those quotes speak to the truth of G.I. Joe — a truth that I think the general population is completely unaware of, and a truth that I think a sizable portion of the franchise's "super-fans" have willfully forgotten: G.I. Joe is a subversive, satirical, anti-fascist science-fiction franchise grounded in a sincere appreciation of character and devotion to diversity.

Yes, franchises grow and change over the years, expanding to encompass more meaning than originally intended. X-Men wasn't about bigotry at first, and Batman is both Adam West and Christian Bale. G.I. Joe was launched by Hasbro in 1964 as a line of 12-inch dolls action figures designed to make money off of parents of boys the same way Mattel's Barbie was with parents of girls: sell the figure, and then make bank off the outfits and accessories. This was the early '60s and these kids were the baby boomers, the kids of parents who lived through/served in World War II. But as the '60s progressed and America furthered its catastrophic involvement in Vietnam, G.I. Joe shifted away from the military in the '70s and more towards being a generic action/adventure toyline, complete with monsters! That shift didn't last long, but it did expand the franchise beyond generic military storytelling.

When Hasbro set its sights on reviving the G.I. Joe brand in the early '80s, they didn't look to the military for guidance — okay, they literally did look to the military for guidance when it came to designing vehicles and weapons. I'm talking spiritual guidance. This was the dawn of the '80s and America still very much associated the military with Vietnam. Hasbro actually took inspiration from science-fiction in both style of figures (using the 3.75" scale made popular by Star Wars) and storytelling. Instead of G.I. Joe being the name of a generic army man that kids customized with little outfits, Hasbro created something much more akin to, well, the Avengers.

G.I. Joe was reimagined as a team of characters with codenames, specialties, weapons, and — once they found the right writer — personalities and backstories. But how was Hasbro going to showcase all of this for a new generation of kids — a Generation X, if you will — who were mainly interested in toys that had movie and TV show tie-ins?

Some context: toy lines and franchises weren't in sync in the late '70s and early '80s. Star Wars toys famously didn't hit stores until almost a year after Star Wars opened in theaters. I'd argue that it was likely the double whammy of G.I. Joe and Masters of the Universe, with toylines that launched in 1982 and cartoons that debuted in 1983, that kickstarted the whole idea of launching toys with cartoons simultaneously. So G.I. Joe had to kind of invent the thing that later toy sensations — Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Dino-Riders, Mighty Morphin Power Rangers — would deploy.

Anyway — Hasbro had an idea of what the new G.I. Joe would be and they wanted to show that off via animated commercials (easier and quicker to produce than a full-length TV episode). But new regulations around toy commercials prohibited excessive use of animation. Toy commercials actually had to show off the toys, and Hasbro thought it would be hard to sell all of these new characters and concepts in a 30-second commercial of real, random kids running around with tiny plastic figures.

Fortunately for Hasbro, the regulations around toy commercials did not apply to commercials for comic books — and comic book production involves a fraction of the time, personnel, and cost of a cartoon. Enter: Marvel Comics, Cobra, and Larry Hama.

First, Cobra: It was the Marvel team who asked Hasbro about the bad guys, as there were no bad guys in Hasbro's initial pitch. Hasbro just assumed that they'd make the good guys and kids would use another company's figures as bad guys. That wasn't going to fly in a comic — what, Marvel was going to publish a comic where the Joes fought a Slinky and Mr. Potato Head? Marvel editor/writer Archie Goodwin is said to have tossed off the name "Cobra," thus changing the course of human history.

When it came to creating the actual comic, Marvel Editor-in-Chief Jim Shooter turned to Larry Hama — apparently after every other editor/writer turned him down. At the time, Hama was a 33-year-old editor at Marvel who was trying to transition to writing full-time. He was himself a Vietnam veteran and an ex-actor, giving him the lived experience and knack for storytelling that one would need to write a brand new comic book from a stack of rather generic, yet still unique, character designs. Hama, who'd just tried to pitch Marvel on a Nick Fury series called Fury Force, folded a lot of those ideas into what would become Marvel's G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero.

Thus came G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero #1, published in March 1982, and the first-ever TV commercial for a comic book.

And if kids just so happen to see some G.I. Joe action figures the next time they're shopping with mom ... well, I guess maybe they'll want them, too!

It was Larry Hama who wrote all the file cards on the backs of the figures, giving life to top-tier icons like Scarlett, Snake Eyes, and [thanks to Archie Goodwin's suggestion] Cobra Commander.

Let me circle back to the statement that set off this history lesson/tangent:

G.I. Joe is a subversive, satirical, anti-fascist science-fiction franchise grounded in a sincere appreciation of character and devotion to diversity.

So, G.I. Joe contains multitudes. It started as the Greatest Generation making dolls of themselves for boomers to play with, moved away from the military and towards adventure as Vietnam heated up, and was reintroduced in the post-Vietnam era to Generation X and elder millennials as a military team with superhero, sci-fi, and even espionage inflections. This new G.I. Joe existed because Hasbro wanted to create characters and went to Marvel Comics — the company known for putting characters at the forefront of superhero storytelling — to get the job done. The first wave of figures included a Black man and a woman, and subsequent waves would include many more people of all backgrounds — and even a couple more women! Like, almost half a dozen eventually!! And Larry Hama's early G.I. Joe issues introduce killer robots, mad scientists, and brainwashing machines while also adhering to strict military protocol; the franchise could operate in multiple modes simultaneously.

My line of thought, though, my reason for writing about a franchise that has been covered endlessly over the last half century, is this: I don't care about the military protocol side of this franchise. I am not interested in the artillery. I care about the vehicles on a purely aesthetic level. I do not care about realism. And in my journeys through the G.I. Joe fandom over the last year, I've found a level of care and attention to detail that is truly awe-inspiring — but I haven't seen enough analysis of G.I. Joe for what I believe it to be: a superhero soap opera... that is rooted in liberalism and champions the awesome power of teamwork and diversity.

If you want G.I. Joe content that, uh, is not that, there's a lot out there (although I don't think as much from official channels as you'd expect; most of the G.I. braintrust have been disowned by segments of the "fandom" for being "too woke"). And there's even a lot of off-brand G.I. Joe content that tries to replicate the franchise's winning formula but coming from the right, and it just doesn't work as well, does it? Does it?

So, that's my approach to these recaps. That's what I see in G.I. Joe. This is the side of G.I. Joe that I want to promote, especially right now. Let's do this.

G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero Mini-Series 1, Episode 1

"The M.A.S.S. Device Part 1: The Cobra Strikes"

Original Airdate: September 12, 1983

Writer: Ron Friedman

Director: Dan Thompson

Cast: Michael Bell, Chris Latta, Arthur Burghardt, B.J. Ward, Morgan Lofting

What an opening — ! If there's one part of G.I. Joe that consistently lives up to your nostalgia, it's the opening sequences. It's essentially a minute-long commercial for every G.I. Joe toy on the shelves, this time for two years' worth of figures and vehicles. And there are actual similarities between this opening and that first commercial for the comic — like the jingle, duh, and the shot of Flash in the firing range, which was reused. The theme song, which was written for and introduced in the comic book commercials, ups the BPM, ditches the galloping percussive noise (y'know, that "More More More" sound), and features a vocal performance that swings for the fences, like the Alice theme but for boys.

The episode — the series! — opens with a dazzling display of what would later be dubbed "girl power." An unidentified pilot is showing off in a new Skystriker (XP-14F), buzzing close to the ground, giving all the men on the tarmac a buzz cut. Duke promises to "kick the mustard out of that crazy hot dog" before realizing said frankfurter is actually Scarlett (B.J. Ward).

Now that we've met Scarlett and I've worked in the word "frankfurter" into this recap, let's talk about gay stuff. The Joes' primary transport might as well have been the Enola Gay, because this show is loaded with big gay subtext. I know a lot of gay men who grew up adoring this franchise (one is writing this recap), and the appeal is as apparent as Dr. Mindbender's codpiece. There are the Joe designs themselves, which — this being the 1980s — are hirsute in so many glorious ways that would never have occurred to toy designers 20 years later. Mustaches are the default here.

Then there's the toy packaging art, a revolutionary development by Hasbro and Werbin & Morrill that laid the foundation for the entire G.I. Joe aesthetic. The art, the images of big, thick, mustachioed men, frequently standing ass-forward towards the viewer, gives big Tom of Finland vibes. Now, artist Hector Garrido was not queer, nor were any of the G.I. Joe artists that followed him as far as I know. But, I mean, look at the butts.

And, actually most importantly, there are the women. Gay men love to lift up a diva, and G.I. Joe had so many of them ... compared to every other '80s cartoon, I mean. The male:female ratio is still hilariously unbalanced. But — this episode has two female characters, Scarlett and Baroness (Morgan Lofting), who are named, crucial to the plot, and instantly iconic. The ranks expand to include Cover Girl, Lady Jaye, Zarana, Pythona, and Jinx — and many of the series' most memorable guest characters are women (Honda Lou West, Satin, Amber, Mara, Raven, Mahia). G.I. Joe was a precursor to X-Men in that it gave kids a lot of women to root for. And that, y'all, is gay facts.

Wow, I swear, we're going to get past the first minute of this episode.

Then Cobra forces blitz Joe HQ, crippling the team's new fleet of Skystrikers. The attack is led by Maj. Bludd (Michael Bell), a new character for 1983 set apart by his helmet, eyepatch, and ... robotic arm (?) which no one ever addresses. I'm sure it's a traumatic memory for him, so, very thoughtful of Cobra. Still, respect where it's due: Bludd scores a victory here! He was sent to destroy the Joes' new fleet of Skystrikers (1983 retail: $14.95) and his squadron of nondescript Cobra jets did the job. All save one are wrecked — the one carrying Duke (also Bell) and Scarlett.

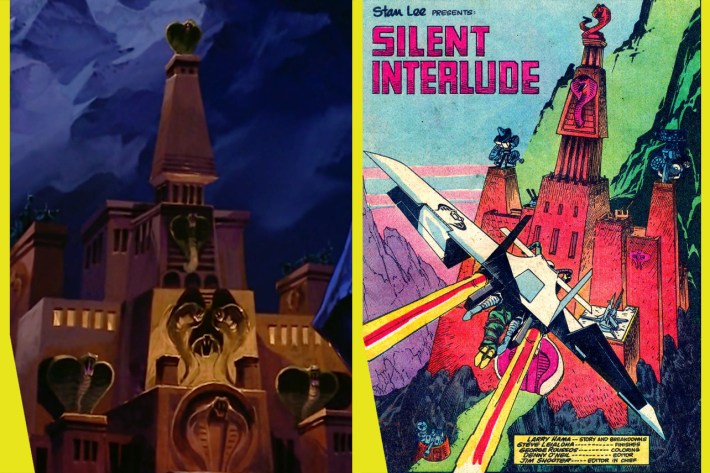

We cut to Cobra HQ, which is introduced as a giant, cobra-adorned castle in the middle of a mountain range in whatever country all '80s cartoon villains reside in, one that's just endless mountains and cliffs and is perpetually midnight. When Destro (Arthur Burghardt) calls this lair a "ridiculously melodramatic location," Cobra Commander (Chris Latta, sounding huskier here as he perfects this soon-to-be-legendary performance) says he built the castle to "guarantee secrecy." Secrecy. The castle is, first and foremost, a castle, and it is covered in snakes. Only a megalomaniac emblazons every building he resides in with what is essentially his name.

A point I need to make because, oh boy, is this going to come up a lot: I love Cobra Commander. He is, no joke, one of my top ten favorite fictional characters in all of human history. He is, IMO, Paul Lynde as cartoon warlord. Now, it is very easy to make comparisons to him and a certain no-brain-celled fascist-in-chief. I just did it. I do, however, think these comparisons are incredibly insulting to Cobra Commander, a man (or, rather, humanoid evolutionary offshoot from a hidden society nestled in the Himalayas) with actual style, charisma, brains, and taste.

Anyway. Destro presents Cobra Commander with three elements (glitter sand, seltzer, and pop rocks) used to power his newly-assembled M.A.S.S. Device. A test of the device flops, I think because they need a way to beam the energy anywhere they want. Cobra Commander blames Destro for wasting his "millions of hard-stolen dollars."

Meanwhile, charged with safeguarding a special satellite dish (sounds useful!) until launch, Gen. Flagg enlists G.I. Joe to test his facility's security. Snake Eyes, Scarlett, and Stalker breeze through security — literally, in Scarlett's case. This feels very much like the X-Men's classic Danger Room opening, a consequence-free action sequence that introduces us to the cast. This really pushes Scarlett, Snake Eyes, and Stalker to the front of an already large ensemble not only as individuals, but as a unit. It's also incredibly commendable to, I guess, Ron Friedman that the three Joes he picks to be the leads are a woman, a Black man, and a white man who never talks.

But unbeknownst to Flagg and the Joes, fellow officer Maj. Juanita Hooper is actually the Baroness. She plants a pog-sized homing beacon on the satellite, linking it to Cobra Commander's side of the transmission. He beams Maj. Bludd and a battalion into the base, and then beams the satellite, soldiers, and Duke (!) back to the Silent Castle.

Now hip to Cobra's plan, knowing it involves transferring molecules via energy beams, Breaker (Latta) finds the world's foremost expert on molecular transference, a Dr. Laszlo Vandermeer (Peter Cullen). The Joes jet to Vandermeer's farm in New England — where he is just outside with an easel, painting, waving hello to all the low-flying jets overhead. But surprise, it's Maj. Bludd! The real Vandermeer is, or rather was (?), a captive of Cobra. The Joes chase off Cobra and rescue Dr. Vandermeer, who says that Cobra stole his secrets of molecular transference, and tells the Joes that they too will need a M.A.S.S. Device if they are to defeat Cobra. Molecular Association of Science Senders? I don't know! What does M.A.S.S. stand for?

Cobra takes control of the world's broadcast signals and shows off by teleporting the Eiffel Tower away, to who knows where!

And back at Cobra's castle, Duke is thrown into the slave pits with a throng of brainwashed captives and forced to fight in the Arena of Sport. His first opponent: a legit f'ing giant. I cannot believe there are G.I. Joe fans who really think this franchise's biggest selling point is the realism.

Personnel Report

First Appearance: Airborne, Baroness, Breaker, Clutch, Cobra Commander, Cobra Officer, Cobra Trooper, Destro, Duke, Flash, Gung-Ho, Maj. Bludd, Rock 'n Roll, Scarlett, Short-Fuze, Snake Eyes, Stalker, Steeler, Tripwire, Wild Bill, Zap

First Line of Dialogue: Baroness, Breaker, Cobra Commander, Destro, Duke, Maj. Bludd, Scarlett, Stalker, Steeler

STRAY BLASTS

It's very easy to poke fun at G.I. Joe's animation, because it is very '80s. But putting it in context, I cannot think of any animated series before G.I. Joe that pulled off action sequences as complex and straight-up dazzling as these. This was 1983. G.I. Joe is John Wick compared to Super Friends. G.I. Joe was produced by Sunbow Productions and Marvel Productions, Ltd., who contracted Toei Animation — the legendary Japanese animation studio responsible for a lot of breakthroughs in anime — to actually bring G.I. Joe to life.

If you leave these recaps wondering why I didn't write more about X or Y character, it's because I'm going to try to focus on the seven characters featured in the corner box of the recap's lead art. Those are the characters — the four Joes and three Cobras — with the most screentime in the episode, as measured by HalfBattle.com. I will get to Baroness, believe me.

I always liked Maj. Bludd — but I can say that about pretty much any Cobra character (although whether or not Bludd is a member of Cobra or merely temping remains unclear at this point). The one thing that I wish had made the transition from the filecard and comic to the cartoon, though? His awful poetry.

Duke is in charge of the Joes, which is weird to me because Hawk — his superior officer — already had a figure and was in charge in the Marvel Comics. Duke even has Hawk's blonde hair (Hawk will be a brunette when he's reintroduced as a general in 1986). I need to find out why Hawk, who was the star of the first commercial, was swapped out for Duke.

Cobra HQ, it should definitely be noted, is what will become known as the Silent Castle. It was named such because it debuted in G.I. Joe #21, a landmark silent issue of the comic, widely hailed as one of the best issues of the '80s.

That issue was released in December 1983, which leads me to assume that Larry Hama was given this design for the cartoon and told to work it into the comic? Another mystery to untangle.

So, are Duke and Scarlett a thing or just flirting? There is undoubtedly chemistry between these two, uh, animated characters. The first thing Scarlett says upon seeing Duke on the tarmac is, "I missed you, Duke." "By that much," he replies. Come on, they have banter!

And since the Joe cast tended to record together going off a script and storyboards, meaning Michael Bell and B.J. Ward were probably next to each other, and since G.I. Joe was then animated to match the energy of those recordings, that might explain why there is a little spark there. Of course, this is in contradiction to what Hama hinted at and then ran with in the comics: Snake Eyes and Scarlet are the franchise's OTP. Since I spent a solid three years as a kid (an eternity) just watching ARAH on repeat before I even knew there was a comic, I'm biased towards Duke. So, one goal of these recaps is to see how much of an Official Couple™ Duke and Scarlett really are.

Thanks to Half the Battle, Yo Joe!, 3D Joes, Joe Guide, and Joepedia for all of the research.

Until next time, reading is half the battle!

Next: "Slave of the Cobra Master"

If you haven't already, consider supporting worker-owned media by subscribing to Pop Heist. We are ad-free and operating outside the algorithm, so all dollars go directly to paying the staff members and writers who make articles like this one possible.