Welcome to the 2025 Heistmas Advent Calendar, a daily drop of pop culture Christmas icons, oddities, and joy. Check back every day from now through December 25 for each daily entry!

It's 2025 and all anyone at Pop Heist can talk about is the Magi! The wise men who visited Jesus at his birth!

Wait, no one here's talking about the Magi? They're like 1/3 of the Christmas story, along with the Holy Family and the Shepherds. 1/4 if you count the animals (believe me, Biblical scholars DO count the animals). Well, it's high time someone here at Pop Heist give those "wise men from the East" some attention, by talking about the actual, real true story of the Magi!

And I'm not just blowing frankincense up your skirt, there are some really bonkers facts (and scholarly conjecture) about the Magi. These are coming from the best book I read in 2025, 1997's Journey of the Magi by Richard C. Trexler. The hardcover's a tad pricey (I got mine secondhand from a seminary in Wisconsin), but the paperback's a liiiiiittle more affordable at $41. Academic books, am I right?

The story of the Magi is explored in Trexler's book, but he also devotes a lot of space to how the Magi were interpreted over time, especially in Epiphany plays that were performed by ecclesiastics and royalty. Even an examination of modern (ala 1997) Magi celebrations is included.

A fantastic book, not too tough to read or find, and full of absolutely mind-blowing and TRUE facts and theories about the Christmas story. But enough talk! Have at you!

There could be more than three Magi

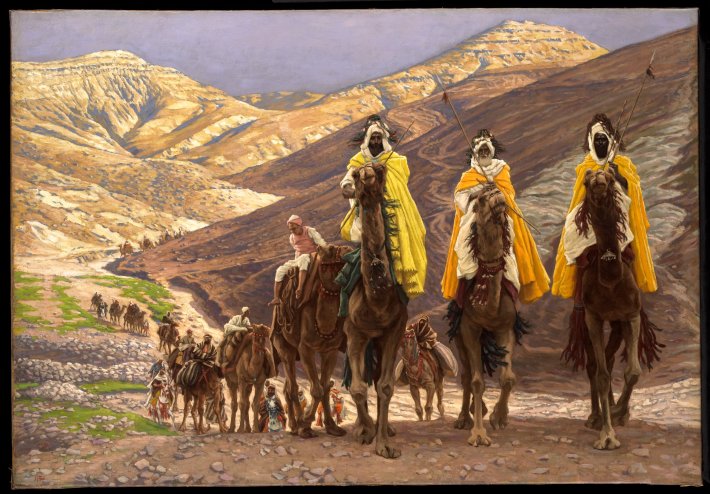

The Magi only appear in the Gospel of Matthew, chapter 2, verses 1-12. They're just referred to as "magi", wise men or philosophers, coming from the East to pay homage. How many of them were there? The author of Matthew doesn't say, but does mention the gifts they brought: gold, frankincense, and myrrh. So you'll see a ton of art with three magi, each bringing one gift apiece. Little humble gifts. But just because there were three gifts doesn't mean that there weren't multiple magi bringing the same gift, or that every magi brought a gift individually. In fact, in many ancient depictions there are more than three! Sometimes two! Sometimes four! Eastern Christian traditions put the number at 12, to draw a parallel between them and the 12 Apostles!

Magi are not kings

A magus, the singular of magi, is not a king. It's a magician, of sorts, and the author of Matthew doesn't say anywhere that they were kings. If they were, King Herod would have probably treated them much differently than just giving them orders to find the baby Jesus. But hey, there's a song about them called "We Three Kings"! They're depicted as kings! Where did this idea come from?

After the books of the New Testament were written and distributed, people began looking through the Hebrew Bible and finding passages that they felt prophesied the events of Jesus's life. One of these was Psalm 72, which talks about foreign kings paying tribute and bringing gifts to the king of the Hebrew nation. In the minds of many, to fulfill this prophecy, the magi needed to also be kings, because the psalm says "kings" and you don't argue with the psalm. But nowhere in Matthew will you find anything saying they were kings.

The gold was a hand-me-down gift

This one's wild. Even if most people can identify frankincense and a fewer number know what myrrh is, gold is universal. And nothing is more universal than the Magi's gold gift to baby Jesus. According to legends that began to pop up in the centuries after 1 CE, the gold was the same gold that was possessed by Moses in the book of Exodus, wound up in the treasure hordes of Alexander the Great, was given to Jesus at his birth, and then also miraculously transformed into the silver that was paid to Judas to deliver Jesus to the Romans 30-some-years later. It's called economic storytelling.

The Magi serve an important literary function

Despite there being "relics" of the three Magi in Cologne Cathedral in Germany, most evidence is against the story being true. But that's not to say that the story in Matthew isn't important. In fact, for first- and second-century Christians, the story of the Magi was an important support for their faith and, more importantly, their conversions.

Think about it this way: You're a Roman citizen around before the time that the Gospel of Matthew was written, about 80 CE. You hear about this neat religion from a traveling Christian missionary. But you're saying to yourself, "This Jesus guy was the King of the Jews, the Jewish Messiah. I'm not Jewish, I worship the Roman gods. I'm interested in this salvation thing that they're selling me, but how could I worship this god that's meant for the Jews?" Thanks to the missionary efforts of people like Paul, the walls between "Jew" and "Gentile" were broken down; Jesus is for everyone, all the people. And how do you illustrate that? Well, you show specifically non-Jews worshiping Jesus at his birth, magi from the East humbling themselves for this Jewish god. So the permission is given: Jesus is for everyone, even the Gentiles.

I bet you're wondering why one of the Magi is Black

There are…two stories as to why the third magus, also called Balthazar, is the Black member of the trio, and amazingly enough, neither is as racist as you might think they'd be.

In the first extra-Biblical tale (called "pseudepigrapha" or "apocrypha"), the Magi were said to be descendants of Noah, the ark guy who restarted humanity after the flood. See what I said about economic storytelling? Everything's connected. And since Noah's sons went off and populated the world, there had to be an explanation why there were Black people in Africa. Enter Noah's son Ham. Ham was Black, Noah had a Black son. So, if the Magi were descendants of Noah, then one of them had to be descended from Ham, and Ham was Black.

Similarly, the second tale assigns each magus to one of the three continents that were acknowledged in the Ancient World. No one knew the Americas, Australia, or Antarctica, all you had were Europe, Asia, and Africa. Since the Magi were supposed to be the non-Jews worshiping Jesus, and these Magi were supposed to represent all the peoples of the known world, one magus from each continent joined the party. Balthazar represented the continent of Africa, so he is depicted in later art as Black. You see this change over time too, as early artistic renderings show the three Magi very uniform in race, as they all were supposed to have come from the same place. But as later myths got added to the story, the art reflected that.

You could pay to be in the Magi

This cracks me up. Christians in the ancient world and the Middle Ages loved to depict the adoration of the Magi in art. It's a great story with some really cool characters who could get away with flashy foreign clothes and body types. And the temptation was always there to…well, if you were the one paying for the painting or the fresco of the sarcophagus, you could ask the artist to pop you into the scene with the famous Eastern trio. It makes you look devout, after all, you're there worshiping the baby Jesus! Of course, some patrons would get ahead of themselves and ask to make themselves larger than the Magi. Ego, man.

There was no massacre of the innocents

This was a big part of Matthew's Gospel, and one of the stranger parts of the New Testament overall. King Herod hears of the Magi who are searching for the "king of the Jews", something he'd like to find out himself, especially if that could jeopardize his rule. But the Magi leave town without snitching on Baby J and Herod loses it, ordering that all children under the age of two be slaughtered in and around Bethlehem. Why Bethlehem? Another prophecy, this time from Micah 5:2 that predicts the Messiah will be born in Bethlehem.

Even though this smacks of Matthew's author's Monday Morning quarterbacking of squeezing old prophecies into his narrative, it's relatively implausible. Widespread slaughters were still taboo, especially by local rulers under Roman rule, especially if their justification was a Hebrew prophecy from an unspecified date. This incident isn't mentioned in any of the historical records aside from Matthew, including the works of contemporary Jewish historian Josephus, who never held back when he was criticizing the Judean powers-that-be.

Most likely this story was inserted for two reasons. One, this slaughter of the innocents was probably meant to parallel the similar massacre of Hebrew babies in Egypt from the book of Exodus, which Moses survived to lead the people. Jesus would then be set up to survive a similar fate and lead the world. And two, the author of Matthew needed to get Jesus and his family to Egypt, once again, to fulfill prophecy from the book of Hosea, "Out of Egypt I have called my son." Narratively, the Holy Family (from Nazareth, which is inconvenient if your Messiah is expected to come from Egypt) needs to get out of Dodge and into Egypt somehow. Hmm, how about they're running for their lives?

The shepherds are less important because it's all about finance

The shepherds don't appear in the Gospel of Matthew. They're in the Gospel of Luke exclusively, but when you're trying to relate one coherent Christmas story to the kids, it all gets jumbled up. While some lore arose over time about the shepherds, the Magi were the ones that really took off in the minds of the public. Their story was reenacted with nobles and royals taking part, but not as the Magi themselves (that was usually notable townspeople or clergy), but as King Herod, showering the Magi with riches and wealth to show how prosperous they were (yeah, it's weird that Herod was the coveted role).

And that's the key: there's money involved. And gifts. The shepherds adored, but they had nothing to give. They didn't travel from far away. They were the lowly Judean peasants who, as Jews, were expected in some way to accept the Messiah. But, again, the Magi were foreigners, Gentiles, who legitimized Jesus as the King of the World. Like any out-of-town guests, they get the lion's share of the attention, especially since they were rich and honored by Herod.

In fact, gift-giving as part of a pageant of the Magi became the norm. These guys were loaded, they're giving gold away. Remember, by the Middle Ages, these were no longer magicians from the East, they had been transformed into wealthy kings.

Then the Americas get discovered and everything gets wonky. How do you explain a magus for each continent when there's now a fourth continent? And they have gold too! Lots of it! Maybe the Americas were the real "Orient". So Christian missionaries start "reminding" the Native Americans (specifically the Incas) that they are descended from royalty. But the church can't just give out gifts like they did in Europe, that would destabilize the colonial plan. So the church's option is to flip the script. They need the Native Americans to give the church gifts, in exchange for blessings.

According to the missionaries, the Magi were poor. So poor. In fact, their gifts are paltry and need to get things in return from Mary. The first magus gives a tiny little bit of gold. "Ah, yes, we [the church] like gold," says Mary, and assures him a place in heaven. The second magus gives myrrh, and Mary's like, "It's kinda rare, but we don't want it. You don't get into heaven, but your prayers will be answered." The third guy with the frankincense is the biggest loser. Everyone's got frankincense, it's a useless gift. He is told that he will wander the Earth without salvation. The lesson to the Incas? GIVE THE CHURCH GOLD. ONLY GOLD.

Oh yeah, this is why the story of "The Little Drummer Boy" is colonialist bullshit.

Check back tomorrow for even more Heistmas Advent Calendar Goodies!

If you haven't already, consider supporting worker-owned media by subscribing to Pop Heist. We are ad-free and operating outside the algorithm, so all dollars go directly to paying the staff members and writers who make articles like this one possible.