Behold, the Cobra-La Corpus — a comprehensive dissection of G.I. Joe's most insidious adversaries. Considered divisive upon their introduction in 1987's G.I. Joe: The Movie, the consensus around the secretive serpentine sect has evolved. From condemnation to celebration, let this unspooling body of work tell the tale.

If you grew up in the '80s and '90s, you owe a lot to Larry Houston. His work on G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero and X-Men: The Animated Series, storyboarding the most memorable scenes of the former and shepherding the latter into groundbreaking, era-defining success, is enough to put him on the same level as all of the greats — but you would not know it to talk to him. Larry Houston is unassuming, humble, and genial, but I would not call him a fan first, creator second. He is a craftsman, a connoisseur, an interpreter and synthesizer of influences — and all that comes across from talking to him. But the energy he radiates? It ... it does feel like that of a fan.

Larry Houston feels like one of us, us fans who grew up investing so much time and energy and love into heroic characters, projecting our own hopes and fears onto them and drawing strength from them. But I think Larry Houston is more than that. I think he feels like one of us because he was the first one of us. It's his work that made all of us into the kind of fans we are today.

Starting in the art department of Filmation's Tarzan/Lone Ranger/Zorro Adventure Hour in 1980, Houston began a streak of work as a storyboard artist and director that is — to undersell it — astonishing. Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends to G.I. Joe and Jem, to The Real Ghostbusters and C.O.P.S., to — hold on for a tidal wave of nostalgia, my fellow early '90s kids — Swamp Thing, Bucky O'Hare, The Pirates of Dark Water, James Bond Jr., Captain Planet, and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. And that's leaving out his most impactful work: bringing X-Men: The Animated Series to life, establishing its characters and tone, shaping its unprecedented storytelling style, and defining the X-Men for an entire generation (or two ... or three).

Personally, Houston has had as much an impact on how my brain thinks of not only action/adventure storytelling, but all serialized, character-driven storytelling — up there with Chris Claremont, Lawrence Kasdan, Peter David, and the Buffy writers. However, that's not the vibe of any chat with Larry Houston. The man loves what he does and what he did, and he's eager to talk about all of it. But what struck me most in talking with Houston for this compendium of all things Cobra-La and the making of G.I. Joe: The Movie is how — while in a hurricane of demands and limitations from bigwigs at toy and animation companies in an accelerated schedule — he held onto what matters most: the characters and the story. And that's why I'm sitting here, today, spending over six months of my life researching, interviewing, and writing about a movie that aired on TV in 1987 — because, as you'll soon read, Larry Houston made it his mission to make that movie worth all of this. Mission: accomplished.

This interview has been edited for clarity and content

Brett White: What has your experience been with G.I. Joe: The Movie over the years?

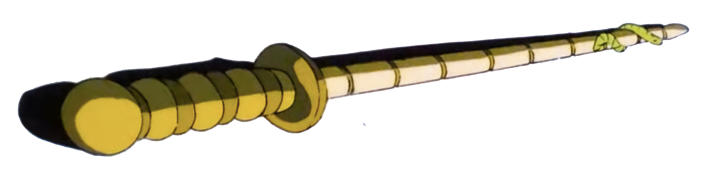

Larry Houston: I've gotten a lot of praise for the opening title that I drew. There were people like, "What's with the sci-fi stuff, the Cobra-La stuff?" The writer who wrote it, Buzz Dixon, he has a lot more insight as to why that happened. For me, it was a lot of fun just to design the opening titles from nothing, basically. And from there I directed the first sequence with the Terror Drome with Pythona. And there's a second sequence involving Sergeant Slaughter going to the Terror Drome. I did both of those sequences

That all makes so much sense, because now, when I'm thinking about it, they're all the most visually striking moments in the movie.

They're both me. They gave me the Terror Drome sequence in the beginning, and when it came up in the script again, they said, "Hey, since you've already storyboarded all the stuff, why don't you take that part?" And I went, "Okay, yeah, that makes sense."

About the opening sequence, from your point of view, is that an opening sequence that stands apart from the movie, or is that the first scene of the movie? Because when we see Cobra Commander next, all of Cobra is yelling about a mission that has failed.

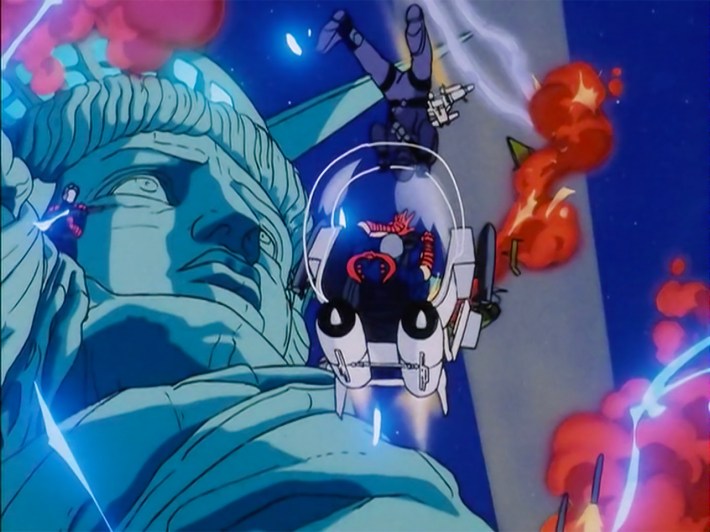

When it was initially designed, it was done as a standalone but they retrofitted dialog to fit that failed mission at the Statue of Liberty. What happened was that we were starting to work on a movie, and then the toy company said, "We think we need an intro" — and that's it. They didn't say anything. So my supervising director, named Don Jurwich, he said, "Make up something." I went home and I was trying to think, what kind of intro can I do for the movie? And on TV — it's back in the '80s, so I don't remember the year they were retrofitting the Statue of Liberty and making it look pretty, and stuff. I went, "A-ha! That's it. I'll take that as the theme. We're celebrating the Statue of Liberty. Cobra comes to F it up, and a battle ensues." So that's where it started.

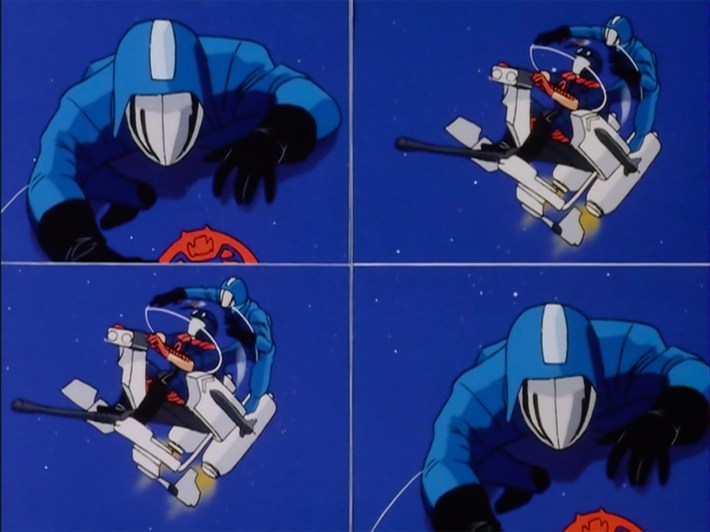

At the very end of the intro, what was the decision behind tiling the four shots of Cobra Commander calling for retreat?

That was that my supervising director. He took the one shot and made it into four.

He thought it added to it. Instead of the one shot, where it would have just been one static shot, it's kind of boring. So he added the other three to make it more, "Cobra retreat!"

Did you know that the theme song was going to be completely different?

We had no song.

Did they make the song to match your storyboard?

Yes, they saw what I had drawn and then they matched the song to what I had done.

The first 10 minutes of that movie are the best G.I. Joe ever was, because I think that the greatness extends into that Terror Drome break-in scene, which is the best action that we'd ever seen in G.I. Joe up to that point. How did you interpret what Buzz Dixon wrote in the script to that amazing sequence?

Normally, what I would do was read what the writer intended it to be, and I try and plus it. How can I take this and make it into a better cinema? With my experience up until that point, I had been directing on Joe since the syndicated series started. So when I got a chance to do that, I know what he wanted. How can I make this even more cinematic? I just use my experience as a storyteller to try and come up with imagery that felt like you're in a real movie.

Did you have any direct inspiration when you were coming up with Pythona's break-in?

In the early '80s, anime was just coming to America and I devoured it as much as possible. There was a guy, Hayao Miyazaki, influenced my cinema an enormous amount. And so between him and other Japanese directors, I was just soaking it in, letting it go into my subconscious. When I was working on the first G.I. Joe mini-series, the opening of the first mini-series, that was me, where you see just the shadows of the jets come in. I did that entire opening combat sequence. And then when they go up to the Cobra castle, and they have to put their hand in the snake's mouth and all that stuff, that was all me.

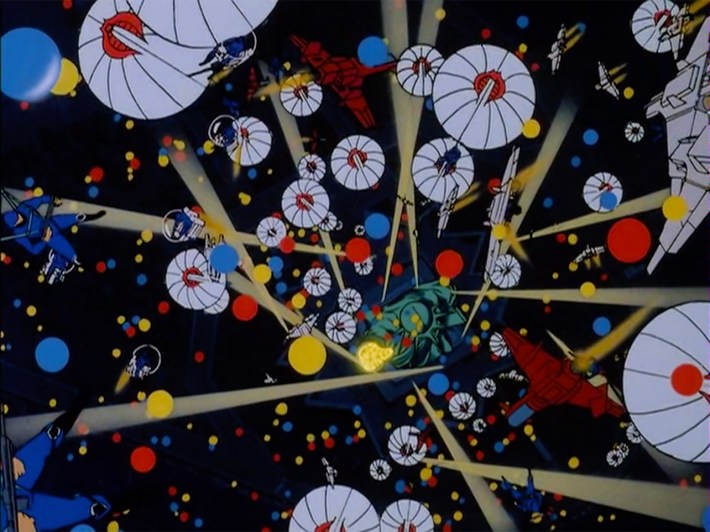

Let me just throw in the kitchen sink and see what comes back, and I did not expect — they put all the damn balloons into the shot. I was like, "Holy shit. They did everything."

I don't think people appreciate how revolutionary G.I. Joe was in that specific way. If you think about what was happening right before G.I. Joe, it's like, Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends. No shade to that very fun show, but G.I. Joe took TV animation to a cinematic level.

Yeah, I worked on on Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends, but I wasn't in charge of it. I was just one person, one of the storyboard artists. And they'd break [episodes] into three acts, so there'd be three storyboard artists. We take our sequence and try and make it as best we could. When I got to be on G.I. Joe, I got to be in charge of the whole show so I could shape the entire narrative and visuals to match what I wanted the final product to be.

So when you were storyboarding that opening, I assume you had the character designs. Did you know what Pythona looked like?

Oh yeah.

Who designed her? Was it Russ Heath that designed all those characters?

Yes, Russ Heath was the designer of all the characters — I should say, most of the characters. I mean, he had assistants and other directors to take care of some of the incidentals and other characters, but it was mainly Russ Heath.

Could you tell that this movie was gonna be weird?

Oh yeah, because when I read the whole script, I was like, "Okay, they're going in a new direction. Okay, Cobra-La, all right. We'll see what happens with this." But you just try and take the the approved script, because this is a script that the toy company approved, and go with it and see how we can make it better and better.

The way you intercut the the impromptu trial of Cobra Commander with Pythona's break-in — little moments you were able to convey, like when Cobra Commander sees her but he tells everyone to go in a different direction. How much time does it take you to think of all those little moments?

At that point in my directing and storyboarding, a lot of it was instinctive. I would get to a point and see where the script's going and then it'll be really cool if I did this, like you're describing, like the mirror image he sees the bad guy going that way, and he says, "Okay, no, let's go this way," because he has this ulterior motive.

I was just having fun trying to make it the best cinema I could, utilizing all of the anime techniques I had evolved into my style. Anime really helped me a lot, because up until that point everything was like Hanna-Barbera, you know, left and right, all that kind of stuff. So Miyazaki and other directors got a chance to simulate 3D in 2D, so I would study that over and over again, seeing how they did it so we could replicate that in domestic shows that I was working on.

What I love about the break-in sequence is the endless list of obstacles that Pythona has to fight through. What was the reaction when you showed people these storyboards?

My supervising director had a lot of confidence that I could figure it out, because it's written down, and so I got to try and make it into something that you can see. I just let my imagination guide me. When I'm working on a storyboard like that, I have no idea what I'm going to draw. It just comes to me. When I put my pencil to paper, I started drawing claws coming in, the platform she's standing on is reminiscent of Empire Strikes Back, Darth Vader's up here, the bad guys are down here.

It all just came to me, and then when Don saw it, he said, "Yeah, we'll go with what you set up because it works. It's clear storytelling."

It is so much more involved than anything G.I. Joe had done, but y'all had a lot longer lead time for the movie than you did for the normal episodes.

Oh yeah, more time to think it through, refine stuff, make this a little bit more on point.

And you were working on the movie at the same time as Season 2, all before Season 1 had even premiered. It's crazy how much y'all were being asked to do at the same time.

Yeah, I was given the Transformers movie first. And I'm a very collaborative director. I like to take the script and improve on it, and add to it to make it better. When I read the script for the Transformers movie, there were parts I wanted to change. And the director, Nelson Shin, I talked to him about it. He said, "No, no, no, just follow script. Follow the script." So I handed it back to him, and said, "I'll work for G.I. Joe," and that's all. I waited, I think the G.I. Joe script came maybe a month or two later, or something like that. That's when I started working on the G.I. Joe movie. And the supervising director on that was Don Jurwich, and he was a lot more open to me interpreting the script and making it even more fun. So that was a lucky choice I made.

I was just having fun trying to make it the best cinema I could, utilizing all of the anime techniques I had evolved into my style.

In the later sequence when Sergeant Slaughter and the Renegades break into the Terror Drome, you have a moment where Serpentor backhands Falcon, leaving him bleeding from the mouth. That might be the first instance of blood in G.I. Joe. You were really able to push the boundaries.

Yeah, because it was a movie, we could push up the violence a little bit. They let us get away with some stuff.

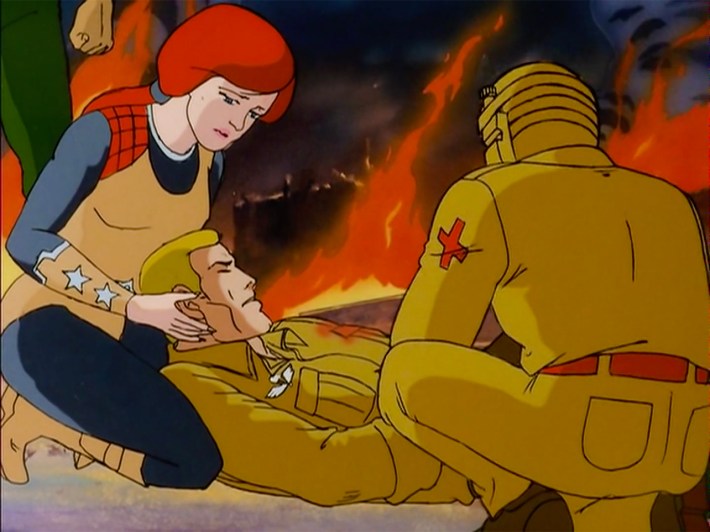

But one thing I probably should bring up is that when we read the first script, it was myself as a director, Boyd Kirkland, Frank Paur and probably another director — but when they kill Duke, we're saying, "Are you sure? Are you going to kill Duke?" We're dealing with people who, I like to say, people who sell plastic, okay? And they're looked at us like, "Yeah, because we're introducing a new line of toys, so he goes out and a new one comes in." And with the script, we asked where's Scarlett. We had set up Scarlett for, like, 65 episodes. She was [Duke's] girlfriend, and stuff. They had a blank look, like, seriously, she was last season's toy, so she wasn't in the script at all. And so I looked at my other directors in the room and, after the toy company left, we said, "We're putting Scarlett in this show on our own." We drew her into the show. We gave her dialogue, and when Duke dies, we made sure she's cradling Duke.

We put that in because we were storytellers, and we knew kids would want that continuity to be there. So we did stuff like that to make it work, because we know what it's like to be a kid watching the show, and we all wanted it to be meaningful and have connection. So yeah, Scarlett wasn't in the show, so we made sure she was in the show.

I love hearing that because as a kid watching the movie, I never noticed that it was all about new characters coming in. As a kid, I'm like, "Low-Light's in the movie a whole lot!" But he just comes out and says, "Showtime." Or Shipwreck, but he just says, "Save my bones for Davy Jones." But because they all had those little moments, it made me feel like they were all had parts in the movie. I love that y'all put that care into it. It worked.

When I did the intro for the movie, I tried my best to showcase in every scene a G.I. Joe that you hardly ever see. So I tried to put them in the background. Cover Girl's barely seen, but I got her into one shot, and Breaker and stuff like that. Just make sure that each character got their moment somewhere in the intro.

Did you ever get to see it on the big screen in the '80s?

Yeah, they rented a theater for the crew and they put it on the big screen, so we finally got a chance to see it all, a gigantic wall of all of our work. I was like, "Wow." Felt great. All of the shows I had been working on up until that point were always TV shows with TV budgets. Then I saw my intro with a theatrical budget — and they drew everything I wanted. To give you an idea: When I was working on the syndicated shows, when I would be drawing stuff, I'd throw in the kitchen sink into almost every scene. But when it goes overseas, they may not have a budget for all that, so you got maybe 50% or less of what you intended the shot to be. But that was because of budgets. When I did the intro, I had the same logic: Let me just throw in the kitchen sink and see what comes back, and I did not expect — they put all the damn balloons into the shot.

I was like, "Holy shit. They did everything." I saw the dailies when it came back, like, there was Hawk on [the Statue of Liberty] going like this [mimes firing machine gun], and you see all the cartridges come out.

Y'all were clearly having fun on G.I. Joe.

That's a word that is not very descriptive, but it actually describes a lot of us. We just had fun. I think we were all in our mid-30s, and we're fanboys from a long time ago. We're working on G.I. Joe and just having fun with the stories and the characters, and trying to recreate the enthusiasm we felt when we were kids, and hopefully translate that into the shows we're working on.

I tell people, I feel very blessed that I got to either work on or be in charge of a lot of action adventure shows in the '80s and '90s. It was 20 years of having just the best, best time ever.

Yeah, and influencing a couple of generations, at least.

I'm very proud that I was able to be in a position that I was to make a difference.

The Cobra-La Corpus

- I: Hasbro’s Lenny Panzica on Bringing Cobra-La to G.I. Joe Classified: “Snake People, Crab Armor, Let’s Go”

- II: "Can I Have Pythona?" — How One Email Changed Skybound's Energon Universe

- III: From Cringe to Canon: G.I. Joe Writer Buzz Dixon Is Finally at Peace With That Movie

- IV: Super7's Brian Flynn is Creating the G.I. Joes You Always Wanted: "Cobra-La Is Really Important for Us"

- V: "Oh, They DO Hate Cobra-La" — How Tim Seeley Gave G.I. Joe's Devils Their Due

- VI: A Better Cinema: Larry Houston Brought Anime to a Real American Hero With G.I. Joe: The Movie

- VII: The Complete History of Cobra-La (COMING SOON)

If you haven't already, consider supporting worker-owned media by subscribing to Pop Heist. We are ad-free and operating outside the algorithm, so all dollars go directly to paying the staff members and writers who make articles like this one possible.