Hey, guess what came out just a few weeks ago! James Gunn's Superman, but if you've been paying any attention at all, you knew that. My Roku replaced the "Search" button with a Superman "S" logo. It's inescapable. Even if you're living under a rock, it's hard to ignore that films based on comics are the touchstones of our 21st century culture.

But where did they start? And what counts as the first comic-based film that is really a movie?

Ultimately, we have to wash our hands of the notion that comic movies stemmed from comic books, and acknowledge that for like 40-plus years before floppy funny issues, comics were a newspaper feature. And they typically weren't the three-panel, reduce-the-size-so-you-can-fit-two-dozen-on-a-page gag strips we have today. Newspaper comics up through the '30s were enormous in comparison, taking up much more space and walking characters through longer comic situations that would be the equivalent of a sketch or extended skit if done on stage.

Time passes, strips shrink, but some of those characters make their way into movies. For every Warren Beatty in Dick Tracy there's a Brooke Shields in Brenda Starr. For every Garfield: The Movie (2004) there's a The Garfield Movie (2024).

Newspaper strips began introducing recurring characters in the mid-1800s. Up until then, printed comics were usually one-off political gags using caricatures of politicians and the like instead of characters the artist created on their own. But once these original characters established themselves, the public started clamoring for more adventures of their favorites. And with the birth of serialized newspaper comics running concurrently with the invention of film, many such characters made the jump into live action.

The problem we face now in 2025 is that so many of these early films are lost media, either not preserved properly or only a few copies made and then misplaced. So many of these shorts are just … gone. We know about them from descriptions in newspapers and magazines of the time, or, if we're lucky, still photos taken from the film or on the set.

Take, for example, Ally Sloper, a British tramp character who debuted all the way back in 1867. Ally Sloper appeared in a 75-foot silent film in 1898, about a minute long. It's gone. It doesn't exist anymore. We know that George Smith directed it, but the cast list is gone. IMDB describes it as "Man dresses up as a woman, and the film is reversed." Not something James Gunn would be looking to reboot anytime soon, but this is more or less all there is to know about 1898's Ally Sloper film. No stills of the several Ally Sloper films seem to exist before a resurgence in the property with new shorts in 1921.

1898 also saw the debut of a film about The Katzenjammer Kids, The Katzenjammer Kids in School, who'd first appeared in print only just a year prior. The plot is a little more fleshed out, but still only a minute or so long. Set in a schoolhouse, the teacher leaves the classroom for a second, where her charges start a ruckus. When she returns she either trips over a chair or a wire strung between two chairs. That's the entire plot. The Library of Congress may have a copy of this, but it is not available online.

And that's how it goes, up until 1906. Scenes are filmed by a static camera and then shown with minimal editing. There are some nifty camera tricks but little splicing, few changes in location. They're comedy skits, the same as you'd see on a vaudeville stage. It's clear that these are films, but are they movies? If your dad captures your school play with a camcorder (going back to the 1980s here), is that a movie? Or just a filmed scene?

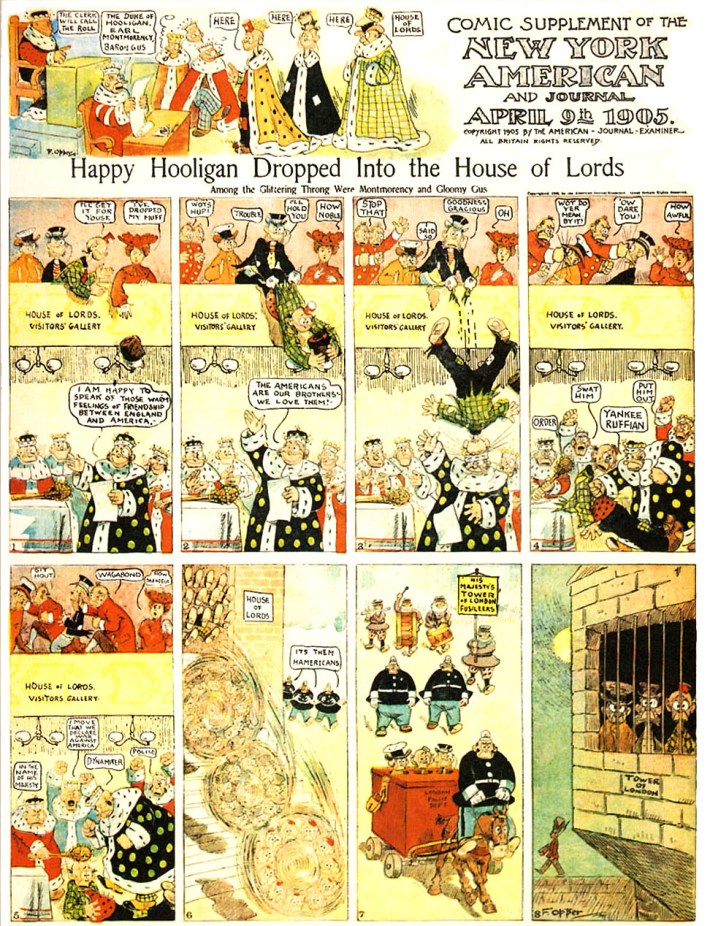

The oldest film that is publicly available, as far as I can tell, is 1900's Happy Hooligan, released the same year the comic debuted, interestingly enough. The hooligan was, once again, a comic tramp, this time with a distinctive stubbly face and a tin can for a hat. Frederick Burr Opper created the hooligan in 1900 and continued the strip for another 32 years! It was popular! And it got a series of super short films starting in 1900, only two of which seem to exist for public consumption.

The Happy Hooligan, or The Happy Hooligan Interferes as it is sometimes called, is one of those single gag shorts that was accomplished by setting up a camera and filming a single scene. The hooligan, with his trademark can for a hat, is enjoying an organ grinder under an open window. A woman inside doesn't like the organ music and leaves to fetch a pail of water to throw on the musician. While she's away, the organ grinder leaves, a cop comes in to harass the hooligan, and the water ends up on the cop.

It's underwhelming, given today's expectations, but it does have some of the hallmarks of the Happy Hooligan comic strip. The character of the hooligan is actually dressed up in a costume that resembles his comic design. There's definitely something on his head, probably a can. And the reversal of fortunes where the hooligan comes out on top of the law is a theme that ran through Opper's strip time and time again. The case can be made that this is the oldest comic-based film that you can see without filing a request with the Library of Congress.

The other Happy Hooligan film on YouTube is Twentieth Century Tramp, a plotless scene that has special effects but no real point. The hooligan flies a simple balloon/bicycle in the sky over some footage of New York City captured by an airplane. Nothing happens, although some prints end with a large cloud where the bike explodes (?) whereas others just fade to black. The brightness balance is so terrible that the hooligan's head isn't visible, so it's impossible to tell if he's wearing his trademark tin can hat. Most videos of Bigfoot are better quality than this.

There are other films from the same time that purport to be based on comic strips, but after watching them I don't think they'd scratch the fanboy itch of seeing your great fictional heroes on the big screen. 1902 saw multiple shorts based on the comic strip character of "Foxy Grandpa," but in both I've seen they just feature a man dancing who might be a tad older than a man you would ordinarily see dancing. There really isn't any wit to those.

1904's Mr. Jack in the Dressing Room is supposedly based on the comic character "Mr. Jack", a well-to-do anthropomorphic tiger from Jimmy Swinnerton that lasted from 1903 to 1935. The filmmakers dispensed with the tiger-like qualities of the character, so he's just a big guy in a suit. He goes backstage at presumably a burlesque show, has a sip of some alcohol, dances with the girls, and is punished by what is presumably his wife. Again, it's a single scene, no edits, static camera shot. Could be anybody, really.

In 1904, one of these films actually got an editor involved, but I'm on the fence whether it's a comic-based movie or not. It's a cute little 2-minute film called Weary Willie Kisses the Bride, where a tramp starts off in a railroad office, steals a ticket from a sleeping man, and woos a woman after he boards the train. In the end he's caught and tossed from the moving vehicle (well, a dummy is). There are cuts, different locations, and even special effects (the aforementioned dummy). But ... "Weary Willie" isn't a comic strip character. "Nervy Nat" was, from 1903 to 1907, and the film was copyrighted as "Nervy Nat Kisses the Bride," but not released under that title. Without that linkage to the strip, it's just another humorous tramp short with an interchangeable lead. If you don't have faith in your star character, I don't either.

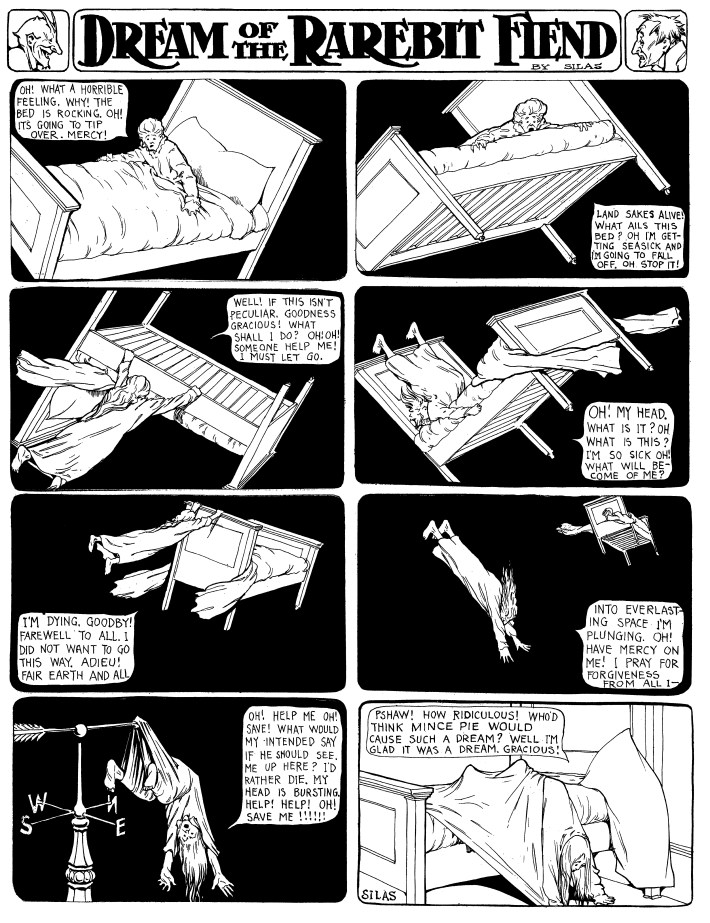

I would argue that the first extant movie based on a comic, book or strip, is 1906's Dream of the Rarebit Fiend. In Rarebit Fiend we get it all: special effects, multiple locations, story beats, more than one gag, models, a full story arc, and, most importantly, continuity with the comic strip it was based on. It's seven minutes long, which is a significant glow-up from the earlier shorts that played out at 75 feet of film and one-and-a-half minutes.

The comic strip Dream of the Rarebit Fiend is one of America's greatest comic strips ever, and that's not hyperbole. It debuted in 1904 and only ran until 1913, but racked up over 800 strips. It was the creation of Winsor McCay, the crown prince of early American comics, known just as well for Rarebit Fiend as he was for Little Nemo in Slumberland, a comic that is still spawning filmed adaptations, and Gertie the Dinosaur, one of the most influential early animated cartoons. (Gertie's place in animation history is so important that there is a statue of her in Walt Disney World's Hollywood Studios theme park.) McCay himself developed several Rarebit Fiend films after this 1906 offering by Edwin S. Porter.

The storyline of the Rarebit Fiend strip was always the same: A regular person, usually upper or middle class, begins the comic in a fairly normal fashion, doing a fairly normal activity. As the panels progress, more and more surreal things happen; buildings stretch and skew, size is inconsistent, nightmarish images appear, people tumble through space. The only limits were McCay's imagination. In the final panel, the protagonist always looks to the reader and regrets eating so much rarebit, or another spicy dish, before going to bed (rarebit being simply a dish of melted cheese on toast).

As you can tell, the story beats are all there, perfectly set up for a recognizable movie adaptation. The journey of Rarebit Fiend is where the genius lies, not the punchline. There is no focal character that needs to be portrayed like the Happy Hooligan or Mr. Jack. And it absolutely screams for groundbreaking special effects.

In the 1906 filmed version of Rarebit Fiend, actor Jack Brawn, as "the fiend," is seen devouring ladleful after ladleful of yummy melted cheese on toast, setting up what viewers will recognize as terrible consequences to follow. He heads home but is so sloshed (from alcohol and rarebit) he needs to anchor himself to a pillar while nausea-inducing projections of a swaying street scene surround him. He's sent on his way by a police officer and heads to bed, only to have his slippers scuttle off out of frame, followed by all his furniture. As he sleeps, he has visions of being poked and prodded by little gremlins, then his bed begins whipping around on its own (thanks to a well-designed model of the room). The bed launches itself into the sky with the fiend holding on for dear life, winding up hanging from a weather vane (an actual adaptation of one of McCay's comics). The film ends with the fiend crashing impressively through the roof with a burst of smoke and debris, regretting his escapades from the night before.

As far as silent short films go, it's amazing. Despite being only seven minutes long, it's the first comic strip adaptation to feel like a finished film and not just dad setting up the camera while the kids do a skit. There are close ups, edits, jump cuts, stunts, humor. It's a straightforward, recognizable adaptation of the McCay strips that follows a storyline that viewers were familiar with from the newspaper. And most importantly, it let the source material keep its voice, instead of contriving a hacky scenario that could apply to any number of characters. I can't say the same for Twentieth-Century Tramp, which is just a man flying over a city (an effect Rarebit Fiend does significantly better).

Whereas other comic strips had been committed to film in the past, Rarebit Fiend was the place where I feel all the current comic book movies can point to as their genesis, that Ur-text that sprung a million imitators and descendants. In 2015 it was entered into the National Film Registry, which selects only 25 films per year, "showcasing the range and diversity of American film heritage to increase awareness for its preservation."

Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, the comic strip, is brilliant and gorgeously illustrated by McCay (writing under the pseudonym "Silas" for some reason). Small press collections have popped up over the years, but it hasn't gotten the big Taschen collection like McCay's Little Nemo has, which is a shame. It more than holds up, the near-obligatory early 1900s racism that plagued all comic strips aside, and is surprisingly entertaining. It requires more of a time commitment to read than, say, Heathcliff, but it's a delightful way to pass an afternoon.

Luckily, the filmed adaptation, the first comic-based movie, only takes seven minutes to watch.

If you haven't already, consider supporting worker-owned media by subscribing to Pop Heist. We are ad-free and operating outside the algorithm, so all dollars go directly to paying the staff members and writers who make articles like this one possible.