In PRESTIGE PREHISTORY, Pop Heist critic Sean T. Collins takes a look at classic TV shows that paved the way for the New Golden Age of Television — challenging, self-contained series from writers and filmmakers determined to push the medium forward by telling stories their own way.

The Prisoner Episode 16 (airdate order) / Episode 16 (AVC order)*

"Once Upon a Time"

Original Airdate: Jan. 25, 1968

Writer: Patrick McGoohan

Director: Patrick McGoohan

Cast: Patrick McGoohan, Leo McKern, Angelo Muscat, Peter Swanwick

You make a show like The Prisoner to make an episode like this.

Written and directed by creator and star Patrick McGoohan, the auteurist masterpiece "Once Upon a Time" is a clear move toward the series' endgame, advancing the overarching plot (!), ending on a cliffhanger (!!!), and promising us that in the next episode both Number Six and we in the audience will, at long last, meet Number One (!!!!!!). That's thrilling enough, and a textbook case of The Prisoner breaking the rules it's established for itself in basically every way conceivable at one point or another.

But as important as all that is, as much as we've been waiting 16 episodes for it to happen, it pales in comparison to the execution. "Once Upon a Time" is one of the most boldly experimental episodes of television ever filmed. You'd have to fast forward to the finale of Twin Peaks Season 2 or the phantasmagorical eighth episode of Twin Peaks Season 3, I think, before you found anything comparable.

There have been other mightily sophisticated, groundbreaking, stylistically innovative shows that weren't made by Patrick McGoohan, Mark Frost, or David Lynch, of course. But to cite two representative examples, The Sopranos' dream episodes are the clear product of the everyday mind of the main character, and Nicholas Winding Refn and Ed Brubaker's magisterially bleak Too Old to Die Young operates in the same basic soporific register the entire time. Only in The Prisoner and Twin Peaks did things already start out "both wonderful and strange," then somehow find a way to become wonderful and strange even by their own immeasurably lofty standards.

The plot is the simplest in the series' history. We learn in the opening credits, which for the first time show a Number Two actually speaking his familiar dialogue, that the new Two is an old one. Leo McKern is unforgettable as the returning leader of the Village, whose tenure, career, and life all appear to be on the line now. Rover, the sinister white security orb, sits in his familiar round chair in the Green Dome, prompting Number Two to yell "I am not an inmate!" at Number One themselves over the phone.

However you slice it, the pressure is on. (Two takes it out on the poor Butler — much more about him later — and turns away his beautiful breakfast.) Reviewing old footage of Number Six's countless words and acts of defiance and rebellion, Number Two tells Number One that enough is enough. It's time to do things his way.

It's time for Degree Absolute.

Look, I'm sorry to do the hard-return look how important this sentence is gimmick twice in one review. (Already!). But when you hear how McKern leans on those words, when you hear the feast his upper-class English elocution makes of its five syllables — "Deg-RRREEE Ab-so-LYUTE" — you'll understand why. This highly fraught psychoanalytical procedure involves regressing the subject to a state of childhood via the Village's usual method, the hypnagogic overhead lamp hanging over Number Six's bed, while Two stalks around the important reciting nursery rhymes.

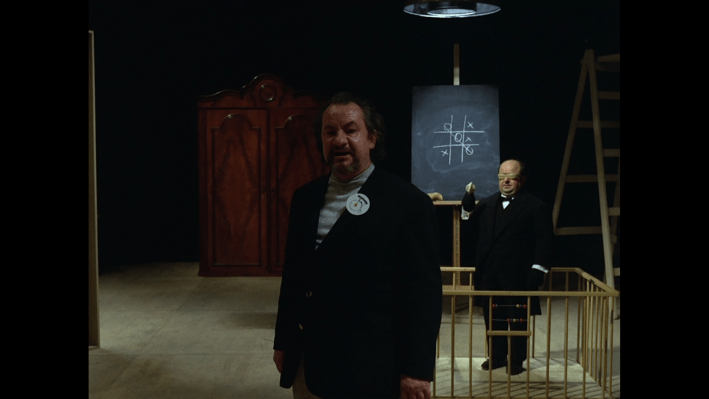

After this, the now childlike Six is brought, half-eaten ice cream cone still in hand, to the place beneath the throne room in the Green Dome: the portentously named Embryo Room. Essentially a large black-box theater, the Embryo Room is the site where Number Two stages what is essentially a two-man show, with the Butler mutely supporting the proceedings at all times.

(The theatrical allusions start earlier, in fact: We learn that before the work day starts, the big wall-screen that shows lava lamp footage in Two's room in the Dome is covered up by red velvet curtains.)

In Degree Absolute, the interrogator and his subject are sealed (with the Butler) in this large, dark, steel-enclosed subterranean chamber. For a predetermined period of time — Number One gives Number Two the apparently short timespan of one week — the interrogator advances the regressed subject through Shakespeare's Seven Ages of Man, from infancy to the "second infancy and oblivion" of old age.

All along the way, Number Two takes the guise of various authority figures to whom Six has answered throughout his life: father, headmaster, coach, boss, judge, enemy commander, and ultimately himself. He'll wear a powdered wig, a bomber's respirator, a boxer's headgear, a fencer's mask, a scholar's mortarboard, whatever it takes to convey the idea he needs to try to crack open his quarry. The action weaves in and out of children's playground equipment, a playground for babies, a rocking horse that inexplicably moves by itself, and a small kitchen and living space enclosed in an iron cage.

The Butler is there too, as anomalous a presence as ever, but never more important to the action. He's always a key part of the set-ups through which Six is marched, shaking rattles, swinging on the swing, dressing up as a cop, fanning the prisoner with a towel, even knocking him unconscious with a cudgel during one of the several points at which he snaps and attacks Number Two rather than answering the eternal question: Why did you resign?

Two had better hope he gets the answer. Even when he makes the call to ask for the procedure to be enacted, out of the view even of the trusted underlings of the Supervisor (the bald and bespectacled Peter Swanwick, whose character has been un-fired following the events of "Hammer Into Anvil"), Number Two knows that Degree Absolute is a danger not just to Number Six, but to he himself. Carrying your own psychological problems into the process, he explains, can lead to a role reversal, in which the prisoner and captor change places. After that, anything can happen.

And if the case is not cracked by the time the seven days are up? Two must either kill or die in his attempt to get it. In other words, unless Six is broken and remade into one of the Village's loyal servants — potentially a better one even than Number Two, according to none other than Two himself — one of the two men won't survive the ordeal.

Since there's one episode left, you can guess who comes out on top. Restoring and reclaiming control of his adult mind, Six turns the tables, locking up Two in the cage and taunting him with his own fear of failure. After watching this magnificent man get broken down to a baby and brought back to adulthood only to be screamed at by Two playacting as a Nazi interrogator, the schadenfreude is delightful.

It's delightful right up until the point it becomes disturbing. When the two men discover that only five minutes are left before the week is up, a triumphant Six, knowing he won't be broken, starts counting down along with the clock as the final minutes tick by. As a disembodied voice shouts "DIE! DIE! DIE!" at Six, Number Two drops dead of poison — or is it fear? — when the clock strikes zero.

It finally happened. A battle between Number Six and a Number Two turned fatal. But Six is not executed for this transgression. He's rewarded.

"Congratulations," says the Supervisor, entering the Embryo Room now that the time has elapsed and the impenetrable doors have unsealed. After stating they'll need Number Two's body for "evidence," this consummate professional has a simple question for Number Six, who I think may now be the new Number Two for real: "What do you desire?"

"Number One," Six replies.

"I'll take you," says the Supervisor. The men exit the room down the strange steel-arched corridor that led to it originally. The end.

Only it's not the end. After Six and the Supervisor exit (and the Butler vanishes), the camera sweeps over the vacant set. It's an island of light in a seat of blackness, in which the classroom blackboard, the after-school mini-car, the playground see-saw, all of it, stands out with surreal vividness. If you feel the appeal of that shot in your gut, you'll understand why the whole thing works.

Within that void, McGoohan, McKern, and Muscat conjure forth an honest-to-god creation. Degree Absolute is a new world, one we've never seen before. It has its own rules for basically every aspect of filmmaking. Traditional and abrupt, avant-garde edits make the rhythm disorienting and unpredictable. The set and props call attention to themselves even by the standards of the show's bold design choices. Brendan J. Stafford's cinematography creates a sense of intimidating depth even on an enclosed set.

But nothing stands out more than McGoohan and McKern themselves. It's the acting that gives the episode its musculature and its magic.

There's no way of knowing how apocryphally the semi-official stories of McKern suffering a nervous breakdown and/or heart attack and both men nearing some kind of transcendent state of psychosis while filming should be taken. Once you've seen what they're doing, though, nearly any level of suffering on their part can be believed.

Ably assisted by Muscat as a physical presence on screen, a stoic yin to their bombastic yang, McKern and McGoohan take the whole thing on their shoulders and hoist that motherfucker high until they collapse from exhaustion. Acting sometimes as friends and sometimes as enemies and sometimes as fellow inmates in the same asylum, the two achieve a fusion of purpose that really has no point of comparison in any other show I've ever watched.

There's a glimmer of insanity in the eyes of both men, McGoohan's as piercingly blue as the Night King's, McKern's mesmerizingly mismatched in pupil dilation and direction. Sweat blossoms from their foreheads like poison from some unknown jungle flower. They talk in a sort of rhythmic, repetitive gibberish that recalls Beckett, as does their predicament, which feels Waiting for Godot in tone, albeit No Exit in nature. The dialogue is driven as much by involuntary tics, like Number Six's total inability to say his number aloud or his tendency to erupt into screams, as it is by actual ideas.

(In an alarming incident that precedes Degree Absolute, Six appears to be headed down this road already when he accosts a random Villager on the street seemingly just to make a scene. It seems we were headed for some new stage of his imprisonment, whether or not a Number Two decided to escalate the affair on his own.)

Yet through all this madness, we get more insight into Number Six than we've ever gotten before. We get the reason he resigned: "For peace. For peace of mind."

Ironically, given that accepting this rationale would have saved his life, Number Two rejects it out of hand. After all, Six accepted his job as an agent for — a numerical unit of — the government, before he resigned from it. One of Number Two's performance-art interrogations even seems to recreate Six's recruitment, though it's not entirely clear.

Two also points out that Six killed people during the War, and this too is reenacted when the two men dress up as pilots bombing German territory. Two has a hard time accepting the idea that such a man truly lost his taste for killing for Queen and country afterwards; even though in an earlier fencing match Six proved willing to draw blood, he didn't deliver the killing blow when given the chance.

But "for peace of mind" is certainly not a full accounting of the situation. Six gives no hint as to what specific incident caused him to reconsider his career; though he indicated in "A. B. and C." that his decision had been brewing for some time, we don't learn the straw that broke the camel's back.

Any time Number Two asks the brainwashed Six to name names, any names, pertaining to his decision, the prisoner refuses, no matter how juvenile or addled he is at the time. This is a man who knows he hasn't explained himself fully, and that he'll never do so. His reasons, his secrets, are his own. As he puts it, "I'm a fool, not a rat."

In the end, Number Two breaks against this stony resolve not to collaborate, not to conform. Number Six only wants to live a life without domination, either of him or by him. He wants to live as what he is: a free man. Will Number One, the man (?) behind the curtain, grant him his wish?

Tune in Tuesday for our exciting conclusion, same Six-time, same Six-website!

This recap was originally accessible to paid subscribers only, and future recaps in this series are available now for paid subscribers. If you haven't already, consider supporting worker-owned media by subscribing to Pop Heist. We are ad-free and operating outside the algorithm, so all dollars go directly to paying the staff members and writers who make articles like this one possible.