In PRESTIGE PREHISTORY, Pop Heist critic Sean T. Collins takes a look at classic TV shows that paved the way for the New Golden Age of Television — challenging, self-contained series from writers and filmmakers determined to push the medium forward by telling stories their own way.

The Prisoner Episode 10 (airdate order) / Episode 12 (AVC order)*

"Hammer Into Anvil"

Original Airdate: Dec. 1, 1967

Writer: Roger Woddis

Director: Pat Jackson

Cast: Patrick McGoohan, Patrick Cargill, Basil Hoskins, Peter Swanwick, Norman Scace

*NOTE: The Prisoner's proper running order is a matter of dispute; Pop Heist is using the AV Club order for the show

In this episode of The Prisoner, Number Six uses the master's tools to dismantle the master's house.

I've described the Village's primary modus operandi against its recalcitrant prisoner Number Six as judo. The open-air prison's masters use Six's own innate drives and desires — to be his own man, to protect the defenseless, to escape — against him at least more often than they try to thwart or break those drives and desires entirely. Sure, there's the occasional science-fictional mind manipulation involved, but that too speaks to the Village's underlying belief that Six's mind is strong almost beyond belief. Only by turning that strength on itself can they really hope to prevail.

Well, Six does nothing to attempt escape in this episode, an increasingly frequent (lack of) occurrence. Nor does he attempt to get to the bottom of any of the Village's mysteries, from "Who are the prisoners and who are the warders?" to the omnipresent question "Who is Number One?" Instead, he uses judo on the Village rather than the other way around. He takes the nearly manic desire of the new Number Two — to break him — and breaks Number Two with it instead.

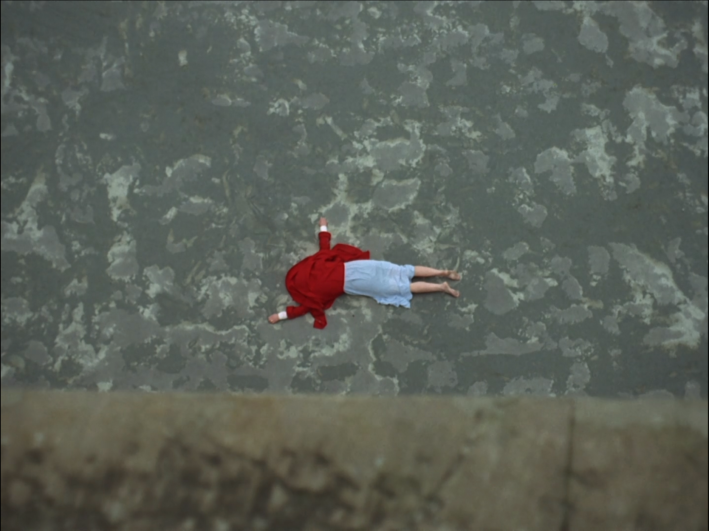

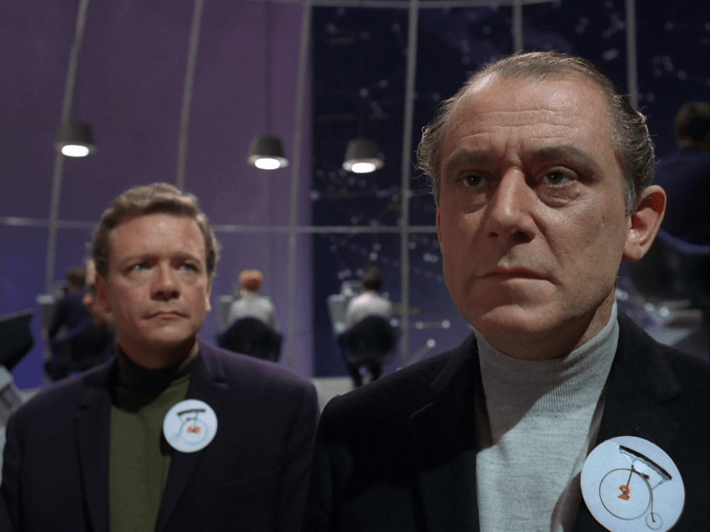

This entire chain of events begins with the grimmest image in the show's history. When the episode begins, the new Number Two (Patrick Cargill, about whom more below), a loathsome figure even by Number Two standards, is in the middle of haranguing Number 73 (Hilary Dwyer), a young woman still in her hospital bed after a serious suicide attempt. Two is after INFORMATION about her husband, and presents her evidence of his philandering in hopes of getting it out of her.

When she still refuses … well, it's not clear what happens. He threatens her, he approaches her, she recoils, and her screams can be heard throughout the Village. There's no evidence of sexual assault — this is not a show that goes there — but it's hard to imagine what else the episode could be implying.

Seventy-Three's screams bring Number Six running right to her hospital room. Wrestling his way past a phalanx of orderlies, he arrives too late to stop Number 73 from springing from her hospital bed and flinging herself from the window to her death. As he gazes down at her body, her red hood covers her face, both obscuring her blood and making its presence unmistakable through visual metaphor.

"You shouldn't have interfered, Number Six," Two says as Six turns from the window. "You'll pay for this."

"No," he replies, absolutely livid. "You will." He spends the rest of the episode ensuring exactly that.

Refusing to meet again with Number Two voluntarily, Six is beaten up and hauled before the man, who carries a sword instead of the usual umbrella, and who uses said sword to threaten Six's eyes — and his life. After the incident with 73, Two is more determined to break Six than ever, and he's clearly not above physical threats. But like all Number Twos, he answers to Number One the way a dog heeds its owner, nervously reassuring his overlord that everything's going smoothly.

A sadistic man who enjoys wielding power over others but who's afraid of his own boss? Oh yes, Number Six can definitely work with this.

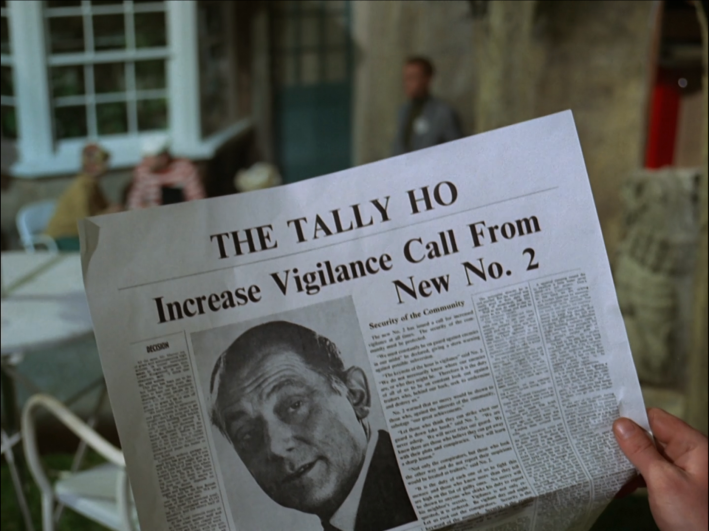

Six's actions in this episode are not unlike those of the Jammers, the subversive group described in "It's Your Funeral," who jam up the works for the Village by planting rumors of fake schemes and plots as distractions. He listens to identical copies of the same album and writes down differences that don't exist. He sends coded notes to no one. He places portentous Don Quixote quotes in the personals of the Village newspaper. He attaches a fake note to a pigeon he sets free. He buys a cuckoo clock and leaves it at Number Two's house, convincing everyone it's a bomb. He dedicates a birthday greeting to himself on the Village radio while posing as a Villager who's now dead. He transmits the lyrics to "Pattycake, Pattycake" out to sea using a mirror and the sun to flash the message in Morse code.

Crucially, he implicates various key Village personnel by making it look like they're in on … whatever the hell it is he's doing, including the Supervisor, the head psychiatrist (Norman Scace), Two's right-hand man Number 14 (Basil Hoskins), and even the humble, mute Butler. Both the Supervisor and the Butler, the show's most familiar faces other than Six himself, receive their walking papers from a furious Number Two for their perceived participation in Six's conspiracy. (The Supervisor is almost pitiful in his dismay; the Butler just quietly collects his things and walks out the door.)

Six's individual actions are baffling, but the underlying idea is simple. Just by writing a note in which he lists his code name as "D.6" rather than simply "6," addressed to a mysterious commanding officer named "X.O.4," Six plants the idea that everything Number Two knows is wrong. He hasn't been sent to the Village to test the loyalties of Number Six. Number Six has been sent to the Village to test his loyalties instead.

Six may be the Village's prisoner, but he's also the Village's student. Time and again, the authorities have employed psychological judo in dealing with our hero, using his most fundamental drives and desires — to protect the innocent, to uncover the identity of the guilty parties, to escape — against him. Nearly every damsel he tries to relieve of distress, every prisoner he befriends or warder he uncovers, and every backbreaking and heartbreaking attempt he makes to get out of there is used either to drive home the Village's omnipotence or deepen his connection to it. It's worked on him over and over. Now the tables have turned.

This isn't the first episode in which Six has eschewed escape in favor of fighting the power. He drove a Number Two out of town in "A Change of Mind"; he thwarted a Number Two's attempt to assassinate his predecessor in "It's Your Funeral"; he ended a Number Two's career by destroying his propagandistic supercomputer in "The General" and beating his sci-fi mind-reading technique in "A. B. and C." That's three Numbers Two who've learned you fuck with Six and he'll seal your fate.

But the moment this asshole drove that poor woman to her death, he made Six's list of things to do today. This isn't Six taking the opportunity to use some elaborate plan concocted by others against the Village, as he does in the four episodes listed above. Indeed, this Number Two barely bothers to try and break Six beyond that initial blade-to-the-eyeball threat, since he's too busy trying to unravel Six's fake conspiracy. No, this isn't Six seizing an opportunity, but a deliberate, premeditated, comprehensive scheme to destroy this man for destroying that woman.

And it works! He falls for the initial note linking Six to an unknown higher-up hook, line, and sinker, and becomes so paranoid as a result that he's his own undoing. Growing more dictatorial and unpredictable by the day, he alternately terrifies and alienates all the Village employees he doesn't shitcan outright. His Psychiatric Director's quietly furious "Thank you" when he’s dismissed from being harangued for no reason is maybe the funniest thing I've ever heard on this show.

Chief among his disgruntled disciples is Number 14, a strapping fellow who seems to have something against (or, honestly, maybe even for) Number Six from the jump. Infuriated by the way Six is making a monkey of him and his boss, he accepts Six's challenge for a kosho match, and gets his red-jumpsuited ass handed to him. At the end of the episode, he attacks Six in his home; a furniture-trashing, glass-smashing brawl straight out of Road House ensues, ending when Six tosses 14 out by hurling him through the window.

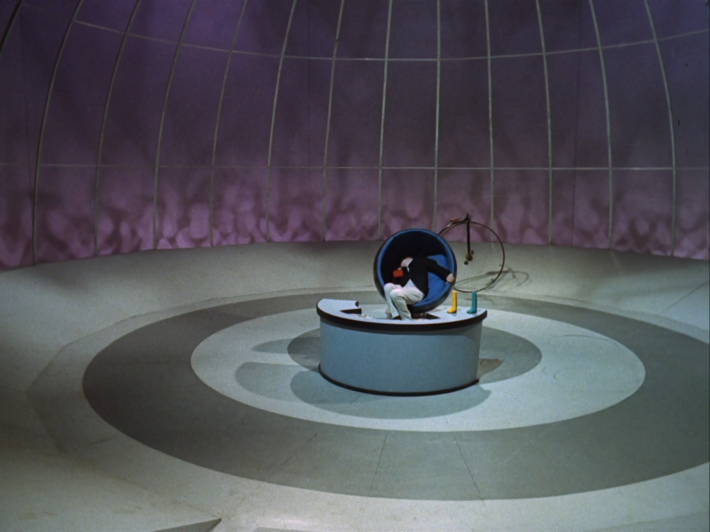

In the end, the cheese stands alone. Actually, the cheese rests his weary head on the Village's prized penny-farthing bicycle, fondling its handlebar. That's how Six finds him when he enters the throne room, since there are no employees left to stop him from doing so.

It's then that slams the trap door shut. Is he a plant, working for the Village's masters to see if Number Two is a traitor? Or is he just a troublemaker, planting false flags to sow confusion and disarray? The answer is that it doesn't matter. Either way, the moment Number Two read the note in which Six claimed to be working for their superiors, the only loyal move to make was to allow the investigation to run its course. By attempting to stop Six and uncover his theoretical collaborators, he proved his unfitness for the position of Number Two even if there was no investigation to begin with.

"You've destroyed me," Two whimpers.

"You've destroyed yourself," Six says. "A character flaw: You're afraid of your masters."

By now, this smug and unlikeable martinet has been reduced to a sweating, pleading, muss-haired wreck. When he begs Six not to report him, Six agrees — and makes Two report himself again, as seen in a striking long shot of Six handing Two the big red phone.

"I have to report a breakdown in Control," he tells Number One. "Number Two must be replaced." A pause as the person on the other line speaks, then: "Yes, this is Number Two reporting." He really has destroyed himself.

As in every case where Number Six gets the better of a Number Two, seeing this smug sadist get his ass handed to him by a guy with no power, no allies, and no weapons except his mind (and occasionally his punches) is enormously satisfying. Indeed, it's never been more so: Actor Patrick Cargill powerfully depicts both the sneering, unearned self-confidence and the petulant, toddler-like tantrum-throwing of the fascist functionary. Interestingly, Cargill portrayed one of Six's potentially compromised colleagues back home in England in "Many Happy Returns," the one who affected skepticism about the Village. I guess now we know why. (To be fair, Prisoner fans and scholars are unsure if the two roles are supposed to be one and the same.) At any rate, you want this guy to get his, worse than maybe any Number Two before him. The shot of 73's dead body on the ground outside the hospital ensures that.

While this episode is not without its share of powerful images like that, it is, however, the least colorful, psychedelic, science-fictional Prisoner we've watched yet. Other than a very low-powered laser beam they use off camera to harmlessly bring down that carrier pigeon, there are no sci-fi gizmos, gadgets, secret rooms, or medical procedures to speak of. The bright stripes of the Villagers' capes and umbrellas never take up the screen like they usually do a few times per ep. This is a down-to-earth version of The Prisoner, in keeping with the down-and-dirty nature of the prisoner's scheme.

In a way, it all comes down to how you interpret the episode's title. It's Number Two who introduces it into the episode: "Amboss oder Hammer sein," he says, quoting Goethe.

"You must be anvil or hammer," Six translates.

"I am going to hammer you!" Two proclaims. But he's favoring Goethe's spin on that phrase. In the untranslated version of the poem from which it comes, it's part of a series of lines in which the poet urges action over passivity. To Goethe, it's better to be the hammer that strikes the hot metal than the anvil that sits around waiting to be struck against.

Number Six, and one imagines Patrick McGoohan himself, favor George Orwell's critique of that use of the phrase. In his essay "Politics and the English Language," Orwell writes about worn-out, misused metaphors. "Another example," he says, "is the hammer and the anvil, now always used with the implication that the anvil gets the worst of it. In real life it is always the anvil that breaks the hammer, never the other way about: A writer who stopped to think what he was saying would avoid perverting the original phrase."

Despite all his scheming and note-planting and trust-undermining, Six doesn't really do anything to take Number Two down in this episode. He's not actually a plant; he's not actually working for a top-secret new commander; he's not actually conspiring with any of the other Villagers on either side of the invisible cage bars. He's just … there, solid and unyielding as ever. Through sheer implacability, he forces Number Two to bang and bang and bang away until there's nothing left of him. In boxing, this is called rope-a-dope, and they've done it time and time again to Number Six. Turnabout is fair play.

Now, I've done a lot of research about this by now, and anywhere it's discussed, a blacksmith will eventually chime in and point out that hammers damage anvils all the time. Anecdotal counterexamples aside, you get the idea, right? Compared to the solid mass of an anvil, a hammer's as flimsy as a conductor's baton. Bang that thing as hard as you can and you're more likely to break the hammer, or even your own arm, than you are the anvil itself. And what is Number Two in the end if not a broken arm of the Village body? Control's strength is finite, but defiance's is not. Tyranny is brittle. Oppression is the mask of fear.

This recap was originally accessible to paid subscribers only, and future recaps in this series are available now for paid subscribers. If you haven't already, consider supporting worker-owned media by subscribing to Pop Heist. We are ad-free and operating outside the algorithm, so all dollars go directly to paying the staff members and writers who make articles like this one possible.